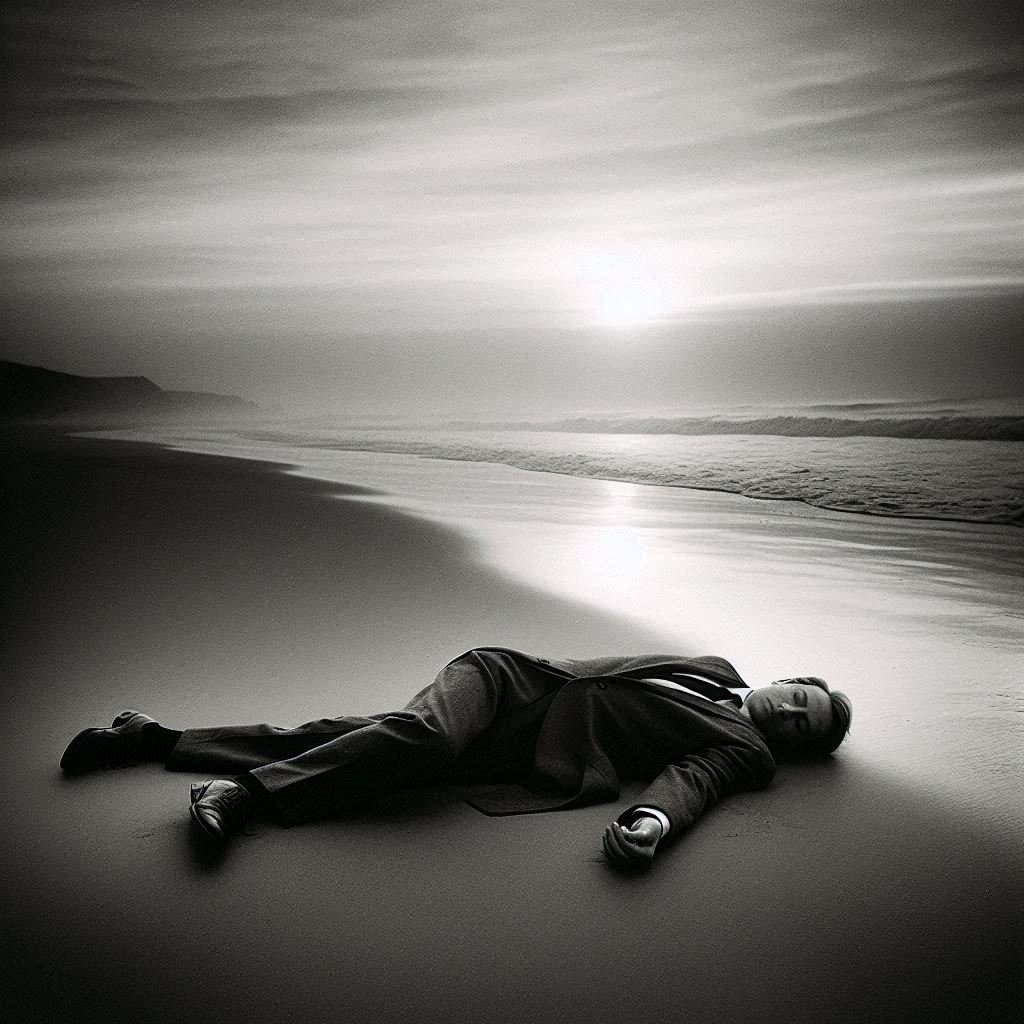

Imagine you’re walking along a quiet beach at dawn. The waves roll in gently, gulls cry above, and the sand is cool beneath your feet. Suddenly, you notice a man lying against the seawall. He looks like he’s just resting, maybe asleep after a long night. But as you get closer, something feels wrong. His head is slumped at an odd angle. His legs are stretched straight, his shoes polished like new. You lean down and realize—he’s not asleep. He’s dead.

That’s what happened on December 1, 1948, at Somerton Beach near Adelaide, Australia. A man in a pressed suit, well-groomed, with no identification, was found lifeless on the sand. No one knew who he was. No one came forward to claim him. And when investigators searched his pockets, they discovered something chilling: a secret code torn from a book of Persian poetry.

This man would become known to the world simply as the Somerton Man. And his story is one of the strangest, most haunting mysteries of the 20th century.

The Discovery

It was just after 6:30 a.m. when two men spotted him. The stranger was sitting upright against the seawall, his legs extended neatly in front of him, his feet crossed. Witnesses from the night before thought they had seen him moving—raising an arm, shifting slightly—so at first, no one panicked.

But when police arrived, the truth was clear. He was dead.

What puzzled investigators was the condition of his body. He wasn’t disheveled or dirty. He wore a suit, a tie, polished shoes, and a clean white shirt. His pockets contained everyday items: a train ticket, bus ticket, a comb, a packet of chewing gum, and a packet of Army Club cigarettes. But there was one glaring problem.

Every single label had been carefully cut out of his clothing. His jacket, shirt, and trousers had no tags. His shoes looked barely worn, as if they hadn’t touched the ground. Whoever this man was, someone didn’t want him identified.

The Autopsy

The autopsy deepened the mystery. Doctors found his organs were congested with blood, and his stomach contained traces of what they believed could be poison. But here’s the problem: no poison was ever identified. His body didn’t show the classic signs of strychnine or barbiturates. It was as if he’d been killed by something invisible.

The cause of death was listed as “acute heart failure due to unknown poison.” But if it was poison, why hadn’t they found it? Was it an untraceable substance? Something experimental? Or had nature played a cruel trick, making a natural death look suspicious?

The police weren’t convinced. They suspected espionage.

The Suitcase at the Station

Weeks later, investigators caught their first big break. A brown suitcase, left in storage at Adelaide Railway Station the day before the body was found, was traced back to the Somerton Man. Inside were personal items: clothes, slippers, shaving gear. But just like his suit, every label had been cut out.

There was only one clue left intact: a name written inside one pair of trousers—T. Keane. But when police searched for a T. Keane, they hit a wall. No one by that name was missing. And curiously, none of the clothes with the name tag matched the man’s body size. It was like someone planted the tag as a decoy.

The Tamám Shud Mystery

And then came the most chilling discovery of all.

Months after the autopsy, a tiny scrap of paper was found hidden in a small pocket sewn inside the man’s trousers. On it were two words, printed in elaborate script: Tamám Shud.

The phrase, in Persian, means “It is finished” or “The end.” Police quickly realized it had been torn from a book—the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, a famous collection of poetry. But where was the book?

Incredibly, a man later came forward with a copy he found discarded in the backseat of his car, parked near the crime scene. The final page had a jagged tear, and it matched perfectly with the scrap found on the body. Inside the book were two things: a faint phone number and a strange code, written in capital letters that looked like some kind of cipher.

This wasn’t just a dead man anymore. This was a riddle.

The Nurse and the Phone Number

The phone number scribbled inside the book led police to a woman known as Jestyn, a nurse who lived nearby. She admitted she once owned a copy of the Rubaiyat and had given it to a man years earlier. But when shown the Somerton Man’s face, she reacted strangely. Witnesses said she nearly fainted.

She denied knowing him, but investigators weren’t so sure. Who was she protecting? Herself? Or him?

Adding to the strangeness, the nurse had once been linked to an Australian army officer named Alf Boxall, to whom she had also given a copy of the Rubaiyat. Investigators briefly wondered if the dead man was Boxall. But when they tracked him down, alive and well, holding his copy of the book—complete with an intact last page—the mystery only deepened.

The Code

And then there was the code.

On the inside back cover of the book, scrawled faintly in pencil, were five lines of random letters:

WRGOABABD

MLIAOI

WTBIMPANETP

MLIABOAIAQC

ITTMTSAMSTGAB

To this day, no one has ever cracked it. Cryptographers around the world have tried—military experts, amateur codebreakers, even university teams. Some think it’s a one-time pad, a code that can only be solved with a specific key. Others say it’s just gibberish, a meaningless scribble.

But when paired with the nurse, the mysterious book, and the possibility of poison, the code looked a lot like the fingerprints of espionage.

Espionage Theories

This was 1948—the Cold War had just begun. Australia was heavily involved in intelligence sharing with Britain and the United States. Soviet spies were active in the region.

Was the Somerton Man a spy?

Some think so. His untraceable clothing, the poison with no antidote, the secret code—all point to intelligence work. The location also raised eyebrows. Not far from Adelaide was the Woomera Test Range, a highly classified site for missile testing. If he was a spy, had he been caught and silenced?

Others point to the unusual condition of his body. His spleen was three times its normal size, his stomach engorged. Some doctors believe this suggests a rare poison—one that would have been almost undetectable at the time. Exactly the kind of tool a spy would use.

But if he was a spy, why leave his body in plain sight? Why not make it look like an accident? Unless, of course, it was meant to send a message.

Dead Ends and False Leads

For decades, investigators chased every possible lead. A ballet dancer missing from Sydney. A logger from Queensland. An American sailor. Each time, DNA or dental records ruled them out.

In 1978, Australian writer Stuart Littlemore aired a television special suggesting the Somerton Man might have been poisoned with digitalis, a drug derived from foxglove plants. But without samples, the theory couldn’t be proven.

In the 1990s, Professor Derek Abbott of the University of Adelaide became fascinated with the case. He noted the man’s ears had a rare genetic trait, and his teeth were missing two lateral incisors—another unusual feature. If a family could be found with the same traits, it might unlock the puzzle.

DNA and a Breakthrough

For decades, the Somerton Man’s body lay in an unmarked grave. But in 2021, authorities finally exhumed him. Using advanced DNA testing, genealogists worked to trace his ancestry.

In 2022, Professor Abbott announced a breakthrough. The Somerton Man, he claimed, was likely a man named Carl “Charles” Webb, born in Melbourne in 1905. Webb was an electrical engineer with a troubled marriage. Records suggest he left his wife and disappeared.

At first glance, the identification seemed to solve the mystery. But questions piled up fast. If he was just Charles Webb, why the secret code? Why the labels cut from his clothes? Why the poison?

Theories exploded again. Some say Webb lived a double life, dabbling in gambling or crime. Others insist the DNA match isn’t enough—that the real story is still hidden.

Why the Mystery Endures

The Somerton Man isn’t just about a corpse on a beach. It’s about the secrets he carried. The code that no one can solve. The nurse who went pale at the sight of him. The words Tamám Shud tucked in his pocket, like a final message from the grave: It is finished.

Even if Charles Webb was his name, it doesn’t explain the bizarre circumstances of his death. Was he poisoned? Was he a spy? Was he a jilted lover leaving a message in poetry? Or was he someone history will never truly allow us to understand?

The Lasting Haunting

Walk along Somerton Beach today and you’ll see families picnicking, surfers riding the waves, and tourists taking in the view. But if you pause near the seawall and listen, you might feel the echo of that December morning in 1948. A man in a suit, polished shoes, sitting quietly as the tide came in.

No one knew his name. No one claimed his body. And tucked in his pocket, two words that made the mystery eternal: Tamám Shud.